Introduction

In around 1983, I was given a plant by a friend, who had been given one by her father. It was strange looking, with large disk-shaped leaves, and she called it a triffid; neither of us had ever seen one before. It was easy to grow and I propagated several new plants for a few years before trying to find out what it was. The search led me to the Royal Horticultural Society, who sent me a copy of an article which told the plant's story and gave information about its care. I'm not sure which RHS publication it came from; it could be either The Garden or The Plantsman.

I still have that copy and, since the Pilea peperomioides page has been popular, decided to contact the author, Dr Phillip Cribb (his co-author, Leonard Forman, is unfortunately no longer with us), to ask for permission to reproduce it here. He very kindly agreed, so here it is. We hope you find it interesting.

A Chinese puzzle solved - Pilea peperomioides

Most plants introduced to this country come via organised collecting expeditions and are known to science. Phillip Cribb and Leonard Forman write about the mystery surrounding the introduction of a widely cultivated houseplant which was, until recently, unknown to the scientists.

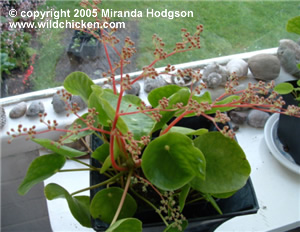

In recent years, few plants have puzzled botanists more than the Chinese money plant. Sterile specimens of it, with its characteristic bright green, fleshy, peltate leaves, appeared regularly at the enquiry desks of Kew, Edinburgh and Wisley from the mid 1970s onwards to be returned with non-committal suggestions such as 'possibly a Peperomia', 'please send flowers next time' or 'we do not identify sterile material'.

Progress on its identification was first made in 1978 when Mrs D. Walport of Northolt sent leaves and an inflorescence of tiny male flowers for identification to Kew. The leaves indeed resembled certain species of Peperomia in the Piperaceae yet the tiny male flowers indicated that it belonged to the stinging nettle family, Urticaceae. Eventually, a diligent search by the Kew botanist Wessel Marais suggested that the plant was a Chinese species of Pilea which had been named in 1912 by the German botanist Friedrich Diels as P. peperomioides, a singularly appropriate name.

Pilea peperomioides had been first collected, as had so many other Chinese plants, by George Forrest in 1906, and again in 1910, in the Tsangshan range which rises to almost 14,000 feet altitude (4,250m) just west of the ancient city of Dali (Tali) in western Yunnan. Although Kew possessed no specimens in its herbarium, Forrest's collections are preserved in Edinburgh and confirmation was quickly obtained from there of the identifications, also incidentally enabling Edinburgh to answer a number of its own enquiries about the same plant.

Over the next few years, further specimens from various parts of the British Isles were sent in for identification and it became apparent that many people were growing this unusual species as a houseplant, passing it on to their friends as cuttings from the readily produced basal shoots, selling them at church bazaars and fetes and so on. Meanwhile, the species was still barely known to scientists who had yet to see female flowers on the living material.

The question which then arose was: how and when did the plant get from the mountains of western Yunnan to this country? In an attempt to find an answer to this mystery it was thought that some publicity would help. We therefore approached Robert Pearson who published an illustrated article in the Sunday Telegraph on 9 January 1983, asking if anyone had any information on the introduction of the plant to Britain they should inform the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Amongst the replies received, one gave the essential lead to what eventually proved to be the answer.

A family, the Sidebottoms, in St Mawes, Cornwall, had first acquired a plant some 20 years previously. The family had a Norwegian au pair, Modil Wigg, and their young daughter, Jill, then aged nine, went to Jaeren in Norway for a holiday with the Wigg family, who gave the girl a small specimen of the plant to bring back to England. This valuable piece of information provided what turned out to be the all important link with Scandinavia, to where the line of enquiry then moved. For a more detailed account, and the first published illustration of P. peperomioides, reference should be made to Alan Radcliffe-Smith's article in the Kew Magazine in 1984.

Botanists from Scandinavia visiting the Kew Herbarium were shown specimens of Pilea peperomioides, but none of them had ever seen it before. They were, however, asked to make enquiries in their own countries. Eventually, the problem came to the attention of Dr Lars Kers of the Bergius Botanic Garden in Stockholm who then realised that the unknown plant he was growing in his own home which he had obtained from a relative in Sweden in 1976 was P. peperomioides. He searched Swedish horticultural literature for further information, but to no avail. As in Britain, the plant was unknown in botanic gardens and to the horticultural trade. He therefore arranged for the plant to be presented on a popular Swedish television programme, a step which proved to be more productive than had been bargained for since it resulted in an avalanche of some 10,000 letters! This at least proved that P. peperomioides was a very popular houseplant in Sweden.

Amongst this massive response came the final link in the extraordinary story. It turned out that a Norwegian missionary, Agnar Espegren, brought the plant to Norway from China in 1946. In 1944 the Norwegian missionaries in China had had to leave. Agnar Espegren and his family, then living in Hunan province, were taken by an American plane to Kunming in Yunnan where they stayed about a week awaiting further transport to India. During this brief stay in Kunming, which is only some 150 miles east of the Dali range, Mr Espegren obtained a live specimen of the plant (possibly from a local market) and packed it in a small box, which was then brought together with his family and all their baggage to Calcutta where they stayed for nearly a year. The Espegren family arrived back in Norway in March 1946 with the plant miraculously still alive.

Mr Espegren subsequently travelled widely in Norway and often gave basal shoots of the plant to friends. In this way the plant was effectively distributed around Norway where it is now widespread as a window sill plant, and where it is known as 'the missionary plant'. This information was provided by the late missionary's son Knut Espegren. From Norway the plant was spread to Sweden, England and no doubt elsewhere. More recently Brian Halliwell of Kew, while on a visit to British Columbia, spotted a plant of P. peperomioides in a house and learnt that it had been bought locally from a garden centre as a 'money plant'. Perhaps 'Chinese money plant' would be a more suitable common name to avoid confusion with the moneywort, Lysimachia nummularioides. It is a most extraordinary story how this Chinese species, while hardly known the western science, was being cultivated in thousands of private homes in Europe as a result of off-shoots being passed on from one person to another.

On a recent visit to western Yunnan with a small party of botanists and gardeners, one of us (P.C.) related the story of Pilea peperomioides to the group as we travelled from Kunming westwards towards Dali inciting them to keep an eye open around Dali for this strange plant. That evening we arrived at the Erhai Hotel in Xiaguan, some 15 km south of Dali. While waiting for our luggage to be unloaded the group wandered around the courtyard where, in the shade of several tall Grevillea robusta trees, a potted display of lilies, rhododendrons and other shrubs were arranged. The centrepiece of this courtyard garden was a shallow well around a tufa-like rock which, to our astonishment, was covered with P. peperomioides, in full flower, beneath the gentle spray of a fountain.

The next morning we saw P. peperomioides being grown as a pot plant everywhere both in Xiaguan and in neighbouring Dali - the Chinese money plant almost, but not quite, at home! Forrest had, indeed, collected it on Tsangshan, which looms over both Xiaguan and Dali at between 7,000 and 9,000 feet altitude (2,200-2,750) growing in shady places on humus-covered boulders.

Dali itself, at around 6,000 feet elevation (11800m), is renowned for its weather, which is spring-like throughout the year, but the peaks of Tsangshan at almost 14,000 feet (4,250m), were still carrying snow on our visit in late April and early May. Therefore, it seems likely that P. peperomioides survives winter temperatures down to freezing. Certainly, in the British Isles it is more likely to flower in spring if kept in unheated conditions. Both male and female inflorescences are produced by the same plant, although the latter are far less frequent. Male flowers are reluctant to open but if held in the palm of the hand or placed in water they burst open releasing puffs of pollen as in other Pilea species such as P. muscosa, the artillery plant.

We have yet to see the Chinese money plant on sale in nurseries here but it must surely feature in them soon. It is one of the easiest of houseplants to grow, flourishing in a peat based compost. It needs frequent watering in warm weather and is easily propagated from the basal shoots which are so readily produced. Further cultural details can be found in the recently published The RHS Encyclopaedia of House Plants by Kenneth Beckett, the first such publication to illustrate it.

The piecing together of this Chinese puzzle has demonstrated how effective the combination of amateur gardener and professional botanist can be as sleuth. For us part of the charm of the Chinese money plant is the story of its strange and convoluted journey from its home in furthest Yunnan to Northolt and beyond.

References

BECKETT, K. 1987. The RHS Encyclopaedia of House Plants. Century-Hutchinson.

RADCLIFFE-SMITH A. 1984. Pilea peperomioides. Kew Magazine, Vol. 1, pp. 14-19.

© Article text copyright Dr Phillip Cribb, Deputy Keeper of the Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey.

Wildchicken gratefully acknowledges the permission of Dr Phillip Cribb to reproduce the text of this article.